The Library: Just a Place for Books or also a Symbol of the Dignity of the Mind?

There are two ways of considering a library. One way is to see it only in terms of its material function as a place where books, magazines, documents, bookcases, and tables should be protected from humidity, fires, and thieves. These documents, magazines and books should also be efficiently organized so that they can easily be found. A building serving as merely a “functional” library should, then, satisfy this practical objective and need not go beyond that end.

To fulfill this practical purpose, a library could look like the building in our first picture. Composed of four successively taller stories, it looks like an immense “chest” with four different-sized drawers designed to neatly organize several different types of objects. And just as drawers can be placed anywhere on furniture, on this building they are represented by the windows. A complete lack of proportion between the parts of this “chest” is the twentieth century’s tribute to extravagance. Thus we have the building that houses the library at the University of California in San Diego.

Let us admit just for the sake of argument that this building meets every requirement for preserving books, magazines and files. However, does it satisfy the needs of men? Even more, the needs of our reader?

* * *

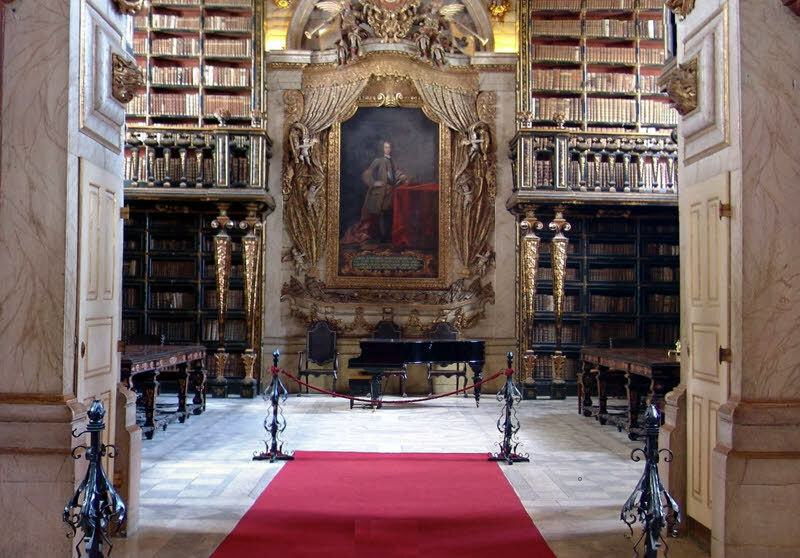

Our second picture represents another conception of the ideal building for a library. While it meets every practical requirement, it also satisfies a higher objective — that the building express the fundamentally noble aspect of reading and studying. The building corresponds to a hierarchy of values that places thinking at the height of human activities, preceded only by prayer. Thus, the building should have, a regal magnificence to the degree possible.

It is this conception that governs the library of Coimbra, Portugal, constructed in the first half of the eighteenth century.

The books are splendidly bound and arranged in huge, solid bookcases, numbered so they can be easily classified and found. Employing all the modern methods of our epoch, this library is completely “functional.” But, on the other hand, the magnificence of its decor makes it seem like both a palace and a church. The picture in the center is that of the King John of Portugal, pays tribute to the monarch to whom we owe this building, and shows just how he regarded the studious, who make-up the highest level in the political and social hierarchy.

The building serves not only the practical objectives of protecting papers, parchments, and bookcases; it also fills a spiritual objective, which is to highlight the prestige of the intellectual in the natural order, and, consequently, in the hierarchy of values of temporal society.

Perhaps someone might argue that the University of California’s library also has a monumental grandeur that in some way is a tribute to the intrinsic nobility of intellectual life.

The objection is not valid. Nobility is not a strictly functional value, and, therefore, it cannot be completely or adequately expressed only in terms of efficiency or bigness. Mere efficiency is suitable, perhaps, for industrial buildings, where production dictates the whole architectural design. However, it is not for buildings destined for ends that transcend the mere practical domain, even while they serve a practical purpose. With all due respect to quantity, it does not express nobility as well as quality does.

(*) This article was originally published in the magazine Catolicismo, Issue #110, Nov 1960. It has been translated and adapted for publication without the author's revision. –Ed.