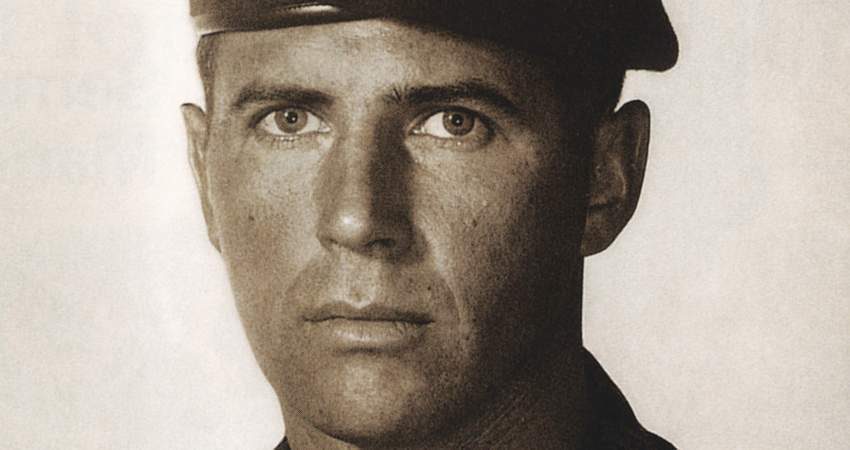

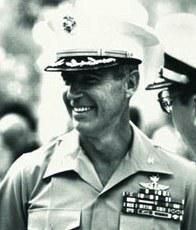

Col. John W. Ripley, USMC: Uncommon Valor

When a society no longer respects and honors the fighting men willing to shed their blood for its principles, the fault lies not with the fighting men but with society itself. Ingratitude is a subtle vice, but a vice nevertheless. Saint Thomas Aquinas says that a debt of gratitude is a moral debt required by virtue. In recent decades, the American view of moral justice has been sadly lacking.

Civil society has not always been so callous. Ever since the rise of Christian culture, Christendom has held its warrior-knights in high esteem. Not only that, they were a basic, creative force that molded Western civilization, as a study of the Crusades will attest. A knight of the Middle Ages went to war in a spirit of self-immolation for the glorification of the Church or the common good of temporal society.

Through the centuries, the admiration and appreciation for the fighting man survived a series of revolutionary and philosophical setbacks that severely affected Christendom; that is, until the arrival of communism. As the latter evil gained in influence, a commensurate decline in the will to fight followed. Time and again, the communists won victories because sufficient support from the printed page and the movie and television screens had effectively disarmed the American and Western fighting spirit. Yet the Pattons and MacArthurs of the world continue to step forward, ready to face death rather than betray the ancient ideals of the warrior. The following story represents our part in honoring that crusading spirit.

Background

During the early 1960s, the communists moved against South Vietnam, which was divided between the communist North and the anticommunist South. By March 1969, the United States had a troop strength in South Vietnam of 541,500. At no time did the American forces make any determined effort to destroy the enemy's capacity for making war. When Richard Nixon entered the White House in January of 1969, he was principally concerned with withdrawing American troops and getting North Vietnam to the peace table. North Vietnam was principally concerned with crushing its enemy.

In studying the peace negotiations of this period, one could easily be lulled into accepting the sophism that to save lives was worth a compromise with the communists. That may seem reasonable only when we forget the famous and oft-quoted warning of Pius XI: "We cannot contemplate without sorrow the heedlessness of those who seem to make light of these imminent dangers, and with solid indifference allow the propagation far and wide of those doctrines that seek by violence and bloodshed the destruction of all society." The enemies of Christendom never stop; they continue to forge ahead peacefully or otherwise. During the Easter Offensive in 1972, Colonel (at the time Captain) John Ripley and the Third Vietnamese Marine Battalion decided to step into the process and bar the way

The Attack

By the Spring of 1972, the North Vietnamese Army (NVA) had completed its buildup and was ready to mount a largescale attack on South Vietnam. As part of the assault, two infantry divisions, 30,000 soldiers with tanks and artillery support, began to cross the boundary between the two countries and attack south along Highway 1, the main north-south artery. They would first have to seize a highway bridge over the major water obstacle, the Cua Viet River just north of the town Dong Ha. Only the Third South Vietnamese Marine Battalion was in a position to block the critical avenue of attack and buy some valuable time. To the 700-man battalion was entrusted the awesome task of stopping, or at least hindering, 30,000 North Vietnamese.

The small number of remaining Americans now in ground combat were assigned to South Vietnamese units as advisers. Few men were better qualified to provide assistance in this nearly impossible assignment than Captain John Ripley of Radford, Virginia. A graduate of the Naval Academy at Annapolis, he led a rifle company through a year of intense combat in 1967. Ripley then served an exchange tour with the British Royal Marines. After returning to U.S. forces, he graduated from both the Army's Airborne and Ranger schools and trained with the Navy's frog men in underwater demolition teams.

Having trained in four elite units, Ripley now joined one of the finest units in the Vietnamese Marine Corps, itself an elite division. Major Le Ba Binh commanded the Third Battalion and had a record every bit as impressive as his American adviser. Wounded on a dozen occasions and decorated many times, he was noted for leading his men from the front as would be expected from a member of the aristocratic warrior class.

The Third Battalion was composed of four rifle companies. Two of them and Captain Ripley spent the night before Easter Sunday at an abandoned combat base just west of Dong Ha. The NVA knew they were there, for they pounded the compound all night long with heavy artillery fire. The rounds came screaming in four or five a minute. The Vietnamese got little sleep; Ripley none.

As the day dawned with an overcast sky, Ripley went out and examined the shell craters. The artillery fire was being directed away from the camp toward Dong Ha. He called his radio man to give a report to his own headquarters. Nha, the young baby-faced Vietnamese, approached with long-range whip antenna waving back and forth. In the months they had fought together, the two had become inseparable. Neither knew the other' s language well, but facial expressions and a common danger made words unnecessary. By that time Nha could read Ripley's mind.

Ripley grabbed the handset. Headquarters relayed the orders, "Fall back on Dong Ha and defend the bridge. I'll give you more information when I can." Binh's bodyguard, a powerfully built, rough individual who was known as "Three-fingered Jack," appeared and told Ripley that Binh wanted him at his command post. Jack was one of those quiet, alert veterans that command respect, a fearful enemy and a welcome ally.

Binh had decided to deploy the two immediately available companies along the south bank of the Cua Viet River. One company would cover the main bridge used by the north-south traffic along Highway 1. It had been built by the Sea Bees five years earlier to carry the heaviest American weapons and equipment, including tanks. The other company would cover a much older bridge just upstream that could only carry light equipment. Binh told his Marines to dig their holes deep. There would be no fall back positions. They had to hold the riverbank.

The two companies formed a column with Binh and Ripley leading the way and headed for the bridge. Another radio message warned, "No time for questions, expect enemy tanks. Out." When they reached Highway 9, which ran along the south riverbank and intersected with Highway 1 at Dong Ha, it was clogged with thousands of refugees and, what was worse, deserters by the hundreds. All of them had only one thought in mind: to get as far away as quickly as possible.

Binh's radio contact informed him that the rest of his battalion plus a regular Army of The Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) tank battalion of about 40 tanks would rendezvous with them one mile west of the town. The medium tanks would be somewhat outgunned by the heavier Soviet T-54s, but they were certainly better than no tank support at all. The tank battalion commander, an ARVN lieutenant colonel, was waiting at the rendezvous point with his American adviser, Major James Smock. The former was less than enthusiastic about staying around and required constant urging to cooperate.

Nha approached Ripley. It was headquarters again: "Our outposts can hear the tanks coming. They are traveling in the scrub terrain just off the roadway, but sooner or later they are going to have to get back on Highway 1 to cross the bridge."

"Don't we have any air up, to tell how many?" Ripley asked.

"None yet. Low ceiling."

"Come on. We must have a thousand feet here."

"Believe me, pal, we are doing all we can. Every fire base up there is catching it and some have gone under. You have to hold the bridge and you have to do it alone. There is nothing here to back you up with."

Ripley's American adviser contact continued to give him bad news. Practically all resistance north of the bridge had been wiped out, which was probably the source of the ARVN deserters clogging the road along with the refugees. Then came the final blow: "We finally got a spotter plane in the air. They have tanks and armored personnel carriers stretched along Highway 1 for miles. Must be at least two hundred."

Ripley shouted back, "We can't stop that many. We have to blow the bridge at Dong Ha." At first his superior on the radio hesitated. The top brass back in Saigon wanted to save the bridge. In the end, Ripley's logic prevailed. A weary voice responded: "You are right. We can't authorize it, but you have to blow that bridge. Get moving that way and we will send some demo up to you."

As they approached Dong Ha, they saw the results of the destructive firepower of the enemy's heavy artillery. Corpses lay dismembered and forgotten along the roadside. Dead livestock and overturned carts were strewn in all directions. Then the artillery started again, countless guns firing together and shells exploding all over the town but only the town. It was being blasted off the map. Everything came to a halt along the highway.

The tank column could not go forward and it could not stay where it was. They backed off to the west and swung around to the southeast and entered what was left of the town from the south. The shelling alternately intensified and then thinned out. At the outskirts, the tank commander refused to go any further but after more arguments agreed to let two tanks accompany the dynamiters. As a parting remark, Binh told Ripley to send a message to his superiors: "There are Vietnamese Marines in Dong Ha. We will fight in Dong Ha. We will die in Dong Ha. As long as one Marine draws a breath of life, Dong Ha will belong to us." A hundred yards from the south end of the bridge, Ripley, Smock and Nha prepared to go on alone.

The Bridge

Captain Ripley studied the bridge through his binoculars. It was built simply but massively. The bridge's basic strength lay in its steel I-beam girders that held up the superstructure. They ran longitudinally, that is, in the direction that the traffic would flow. Each girder stood three feet high, and the flanges extended three to four inches on either side of the vertical member. There were six of them across with about three feet between them. With all that steel, Ripley thought to himself, the Sea Bees could have built a battleship.

These hundred-foot long girders sat on top of massive, steel-reinforced concrete piers (intermediate supports) that rose 20 or 30 feet out of the river. At both sides of the river, the hundred-foot spans connected with the abutments (end supports). In thickness, the piers ran between five and six feet. They would easily have withstood any explosive power then available. The trick was to set the explosives in such a way as to knock one set of girders off the piers, thus dropping a hundred-foot span into the river - no small task but possible by a soldier with the proper training. Fortunately, Captain Ripley had received the necessary training at Ranger School.

Ripley surveyed the scene directly in front of him. Along the near river bank, two companies of Binh's Marines were dug in. Across the river on the north side, there had to be thousands of NVA troops infesting the area. Halfway down his slope, sat a bunker built up with sand bags left over from some previous battle.

The three stood up and made a dash for the bunker. As they ran, the fire from the north side increased in intensity and accuracy. They dove for the bunker just in time. Several shots thudded into the sand bags right in front of them. Ripley decided to leave Nha here, where he could make reports to headquarters just as easily, and not expose him to any more danger than necessary.

He then attracted the attention of a squad leader at the river bank. Through sign language, he asked him to provide cover for the last leg of the journey to the bridge abutment. In a short period of time, Binh's Marines had a steady base of fire hitting NVA positions on the north bank.

The two officers broke from cover and ran straight for the bridge. Again the fire increased as they neared their objective. A heavy, tank machine gun kicked a spray of dirt in front of them. Ripley drove himself harder and harder. When he safely reached the bridge abutment, he almost collapsed from the exertion. He wondered how much longer he would have to keep going.

The Demolition

The explosives were waiting for them, about a dozen pine boxes and an equal number of canvas haversacks. Ripley read the stencil on the three-foot boxes: DEMOLITION-TNT. Each box contained 150 blocks that looked like gray industrial soap. The haversacks contained plastic explosives to be used in conjunction with the TNT.

Ripley decided to cut the girders loose at the first pier, a hundred feet from the abutment. His problems began immediately. The Sea Bees, to prevent sabotage to the under section of the bridge had constructed a chain-link fence on the river side of the abutment topped with three coils of razor wire. Ripley had to crawl over the razor wire.

He chose to work on the downstream side of the bridge. Most of the infantrymen on both banks had dug in upstream, where they had more open space. The Marine captain climbed the fence and grabbed the bottom flanges of the I-beam. He then swung his feet up and hooked his feet on the flange.

He began to inch himself along the beam. His legs took a beating. The razor wire sliced numerous cuts into his legs which bled profusely. Through the wire he went. He was sweating heavily. The sweat rolled into his cuts and they began to burn. At last, he was through the wire.

With 90 feet to go, Ripley let his feet drop free and proceeded by hand-walking down the girder, swinging forward hand to hand. Arriving at the pier, he made an attempt to catapult himself up into the space between the outboard girder and the next one upstream. His legs would not cooperate. His energy was gone. Hanging only from his hands, they began to ache. Either he flipped up between the two beams soon or he would fall into the river. Once again; he almost made it that time. On the third try the heels caught the flanges. Then he twisted around until his body was spread-eagled between the two beams. He set the two haversacks of satchel charges and crawled on his elbows and knees back to Major Smock and the fence.

The major passed the first two boxes of TNT and two more haversacks through the razor wire, which cut the major's hands and arms. Spread-eagled between the two girders, Ripley placed the boxes on the flanges and dragged the load, which weighed more than 180 pounds, back to the pier, where he set the charges to the first boxes of explosives.

Once more he dropped down, holding onto the bottom flanges with only his hands. Swing back and forth, build momentum, leap, grab, catch the heels and then muscle into the channel opening between the next two girders. When his legs and lower body fell below the beams, the communist riflemen fired up into the steel girders, with rounds ricocheting all over. Nothing hit him. Once up into the channel he was safe.

For the next two hours, Ripley worked his way back and forth setting the charges. When he finished, he crawled back through the razor wire, dropped to the ground and lay there for a while gasping for breath. Yet he had only accomplished the first part of the heroic undertaking. The exhausted Marine had to go out there again and set the detonators.

Ripley would have preferred to use electrical blasting caps and wire, but none were to be found, only the old-fashioned percussion caps and primer cord. To make things more difficult, they could not find any crimpers. Ripley had to crimp the caps onto the cord with his teeth. Since the shiny cylinders would explode if gripped too hard in the wrong place, a slight miscalculation would blow his skull apart. He remembered that back in Ranger School an instructor had placed a detonator inside a softball and set it off. The explosion blew the cover, stuffing and string all over the place.

Carefully he placed the cap into his mouth, open end out and put the primer cord in the open end. He slowly bit down. It worked. The second time would be easier, but he had to fight off overconfidence, so he remembered the softball. Now the Marine captain was ready to go back out again.

This time the enemy was waiting for him. He crawled through the razor wire and dropped below the girder. The communists immediately opened fire, far heavier than before with hundreds of rounds bouncing off the girders. Over and over, he prayed to Our Lord Jesus Christ and His Blessed Mother, "Jesus and Mary, get me there! Jesus and Mary, get me there..."

Just as he reached the upstream box of TNT, a tank shell hit the girder about two feet away. The angle was too flat and it bounced off and exploded on the south bank with a violent crash. The vibrations almost knocked him into the river. He set the detonator into the plastic explosive and lit the other end of the cord with a match. He had measured enough cord to allow about thirty minutes.

The girders of the Dong Ha bridge were three feet high and about three feet apart.

Ripley worked his way over to the downstream side and repeated the process and then hand-walked back to the fence. He realized that he had exceeded all normal human endurance, so again turned to God and His Mother: "Jesus and Mary, get me there! Jesus and Mary, get me there..." He climbed back through the razor wire once more and fell to the ground near the abutment in a bloody heap. He was so tired that he could hardly lift his arm.

The major tapped him on the back. "Look what I found. But you won't need them now." He pointed to a box of electrical detonators. Ripley looked at the caps and realized that he had to go through the ordeal under the bridge once again. He had always been taught to rig up a backup charge if one was available, At this point, the substance of a man takes over. His moral integrity triumphs. In fact, throughout the entire ordeal, it was the guiding principle. So he returned again simply because to do the job right demanded it.

While Ripley was again risking his life crawling around underneath the Dong Ha Bridge setting up the backup charges, Smock ran a couple of boxes of TNT down to the smaller bridge and ran back again. Ripley had completed the wiring and lay on the ground next to the abutment, too tired to move. Painfully, he pulled himself up and, with a roll of detonating wire hung over his shoulder, staggered along with Smock back to the bunker where Nha was waiting. The South Vietnamese Marines unleashed a barrage of fire to cover them, yelling encouragement as they went, "Dau-uy Dien! Dau- uy Dien!" (Captain Crazy! Captain Crazy!)

At the bunker Ripley was glad to be reunited with Nha. He looked around for a way to trigger the explosion since they had no blasting box. Nearby was a burned-out truck, but the battery appeared to be in good condition. Ripley tried several combinations to set off the explosives. Nothing worked. The terrible thought of failure came over him.

The captain would have to warn headquarters to give time to others to regroup farther south. He would stay with the Third Marine Battalion. Binh would never pull back. He had already made that clear. The battle-scarred warrior would die at his post with no forethought of death. From across the river, Ripley heard the tanks starting up. The massive assault was ready to begin.

Then the bridge blew. The shock waves came before the noise. The noise arrived, growing louder and louder in a series of explosions that became one huge roar. The entire hundred-foot span dropped into the river, leaving a huge gap in the bridge. The time fuses had done their job after all.

The Aftermath

The battle continued to rage around Dong Ha for days after, but the overwhelming forces of the NVA soon began to wear out the defenders. Most areas in the north and south had crumbled. A large group of communists were pressing down on Dong Ha from the west. Binh's Marines were still dug in and holding, with some of Smock's tanks and armored personnel carriers lending support. Ripley was making desperate calls for artillery support when a barrage of mortar fire raked the area, signaling an all-out attack.

At that moment, a vehicle carrying seven journalists and cameramen raced up. Completely oblivious to what was going on, they jumped out and surrounded Captain Ripley with microphones, asking one silly question after another. Ripley yelled at them, "Get out of here; the NVA are attacking." A mortar round exploded, throwing all of them into a pile on the ground. Ripley crawled out from underneath the bodies. Some were dead; others lay groaning and bleeding.

He looked around; then his heart fell. Nha lay dead with a mortar fragment in his head. Major Smock was severely wounded. All the South Vietnamese vehicles were pulling out. Ripley was able to pile the wounded on them only with difficulty. Nobody was staying around now.

.When he went to load Nha's body on the last tank, it moved away and disappeared. The beleaguered captain looked up and saw the point men of several NVA rifle squads approaching. He was going to die, but he was taking his dead radio man with him. He put Nha's body over his shoulders and started walking, fully expecting to catch a bullet any minute.

He heard rifle fire and looked up. Three-fingered Jack and another Marine were firing away at his assailants. More South Vietnamese Marines came over the embankment directly in front of him and kept the enemy pinned down until he climbed up behind them. Captain Ripley was safe.

A few days later the Third Marine Battalion received orders to break through the encircling enemy and a few weeks after that it was pulled out of action. Of the original 700 men, only 52 survived. By then Smock, Nha and Jack were dead. However, they had succeeded magnificently in their task.

The ARVN regrouped and held a defensive line ten miles south of Dong Ha. Thus the Easter Offensive was stopped because the NVA failed to cross the bridge at Dong Ha. One cannot but wonder that, if a few more men like Captain Ripley, Major Binh, Major Smock, Three-fingered Jack and Nha, the radio man, had dedicated themselves like the Crusaders of old, the communists could have been stopped entirely. As it was, they were stopped for three years.

Watch Col. Ripley's moving funeral here:

To read Col. Ripley's full biography, get a copy of An American Knight by Norman Fulkerson.